Happy Sunday, and happy Easter Sunday to all who celebrate. I’m finally writing about art again! This is the first official post for a “series” on here that will showcase artists, galleries and museums, collections, collectives, etc., that I have connected with in some way. It’s my goal to write about art more regularly, and to practice, get better, and find my rhythm, and this is my newest commitment to that goal.

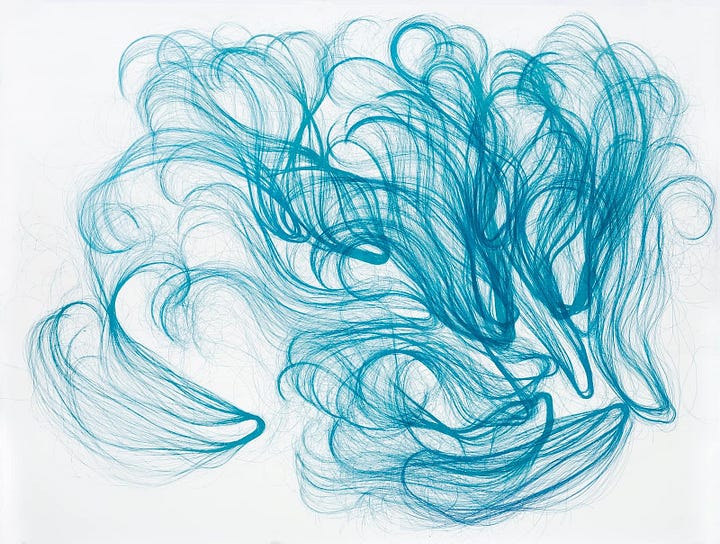

On Saturday March 29th, I went with my dad to the second day of the IFPDA (International Fine Print Dealers Association) Print Fair. While at the fair, one particular booth drew my dad and I in, and we ended up chatting with one of the artists. This was quite special, as many other booths are manned by gallery assistants and owners rather than the artists themselves. The artist’s name is Althea Murphy-Price, and she is a printmaker who specializes in many forms, including screenprinting, lithography, and 3D printing. Her piece “Windows” caught our attention, as the elements it features appear raised off the paper. We talked to Althea for a little while about her technique and process, (for each print of “Windows,” she printed dozens of layers of ink) and I was moved by her creativity, technical knowledge, and her passion for her collective, Black Women of Print.

Althea is a Cohort II member of Black Women of Print, an artist collective of six Black women printmakers that “promotes the visibility of Black women printmakers, via accessible educational outreach, to create an equitable future within the discipline of printmaking.” It was formed in October 2018 by Tanekeya Word to make an “equitable safe place for Black women printmakers who were underrepresented in the discipline of printmaking, a space that is eulogized as democratic.”

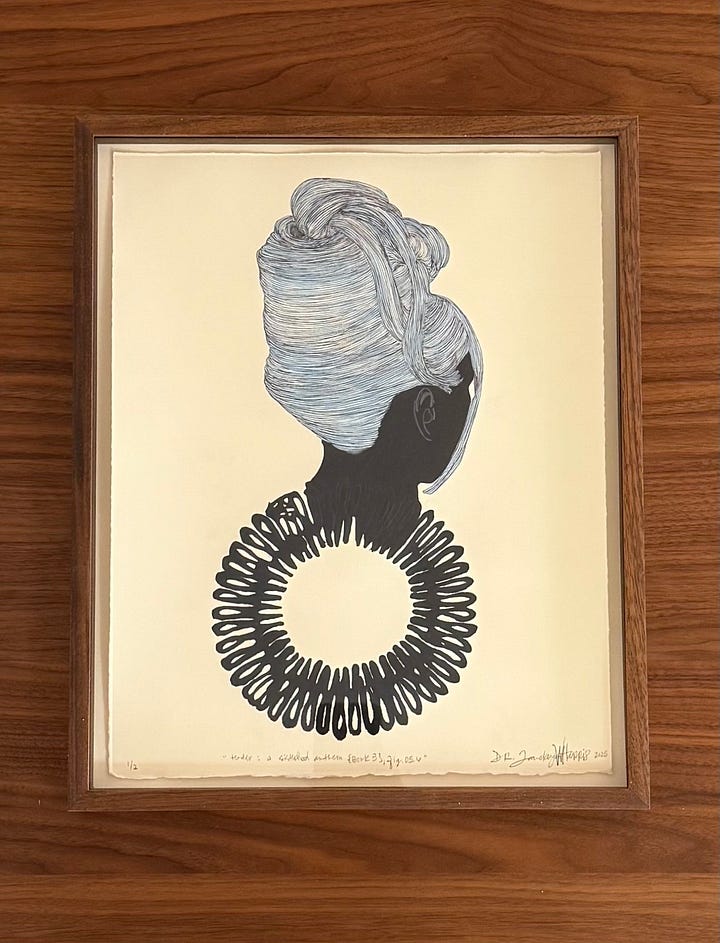

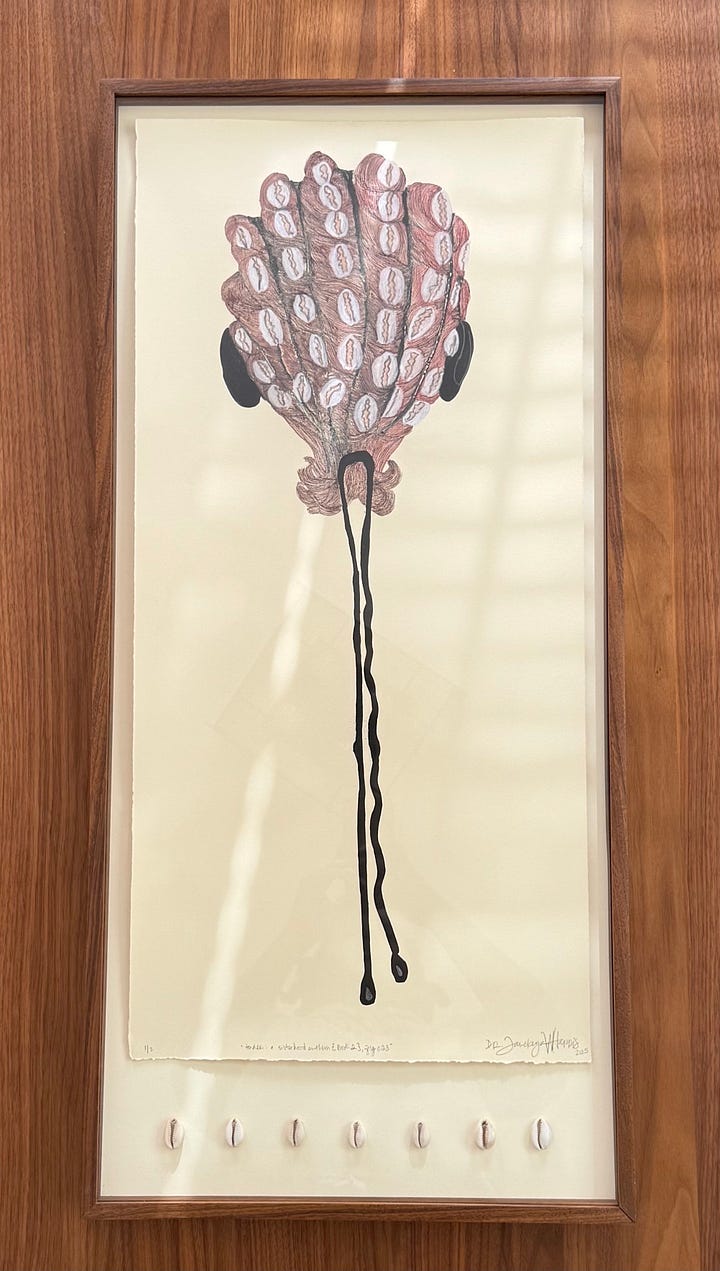

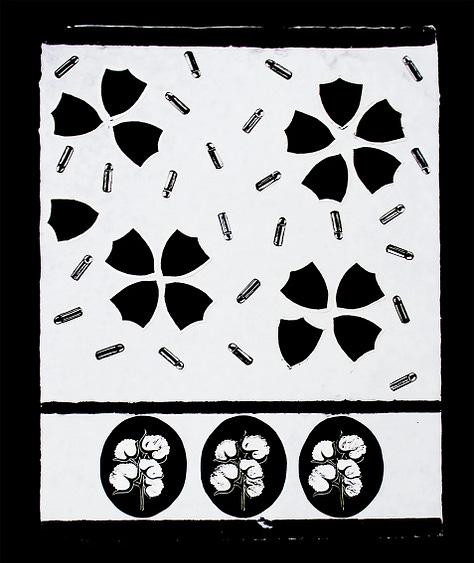

Word’s work “centers the everyday fantastical lives of Black women and girls,” and her monotype prints on display at the IPFDA booth feature hair tools and accessories integrated into the bodies / physical forms of Black women. The prints are surreal in the ways organic and inorganic are merged, and yet they are rooted in the very real significance of hair within Black culture, contemporarily and throughout Black history and memory. The works are titled “tender: a sisterhood anthem”, evoking the emotional tenderness that comes from acts of care such as washing, braiding, and styling hair, often done amongst friends, family, and neighbors, as well as being “tender-headed.” I’ve included photos, from Word’s website, of some of my favorites.

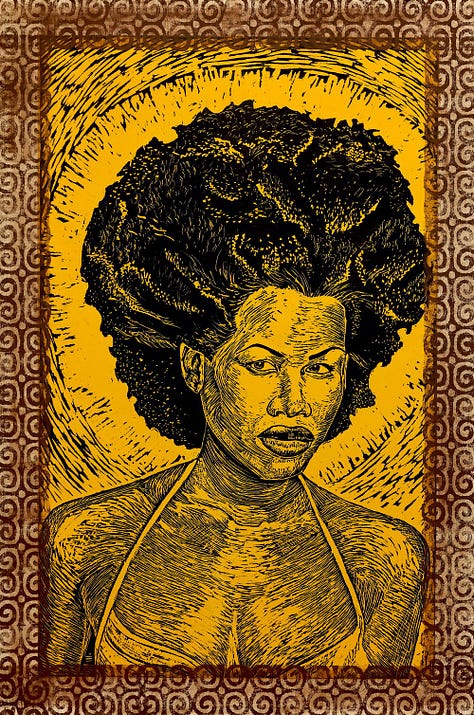

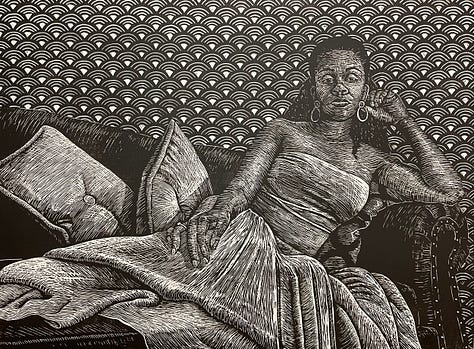

Also featured at the print fair was Latoya Hobbs, a printmaker and painter whose work “deals with figurative imagery that addresses the ideas of beauty, cultural identity, and womanhood as they relate to women of the African Diaspora” (from her website). She is an expert in techniques like woodcut, linoleum cut, and monotype, and she create (mainly) portraits of staggering depth and detail.

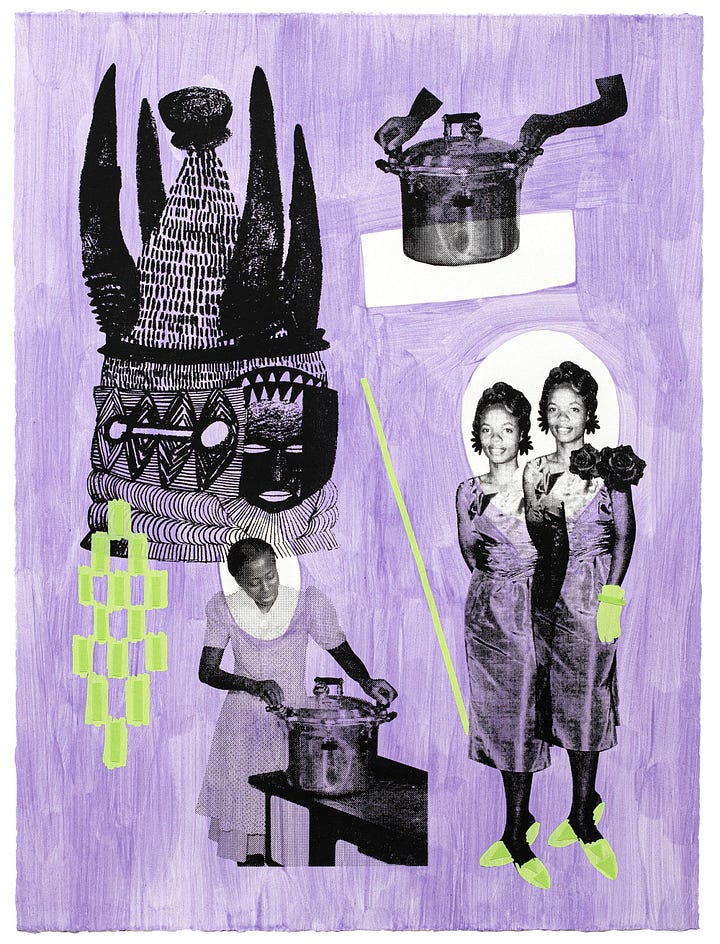

Stephanie Santana, a founding member of the collective, is a printmaker, as well as an textile artist and surface designer, who “constructs tactile narratives, traversing the space between memory and the physical evidence of Black life.” She uses “archival family photographs and documents, often dating from the era of Jim Crow and the American civil rights movement” and “intuitively [layers] printmaking, hand embroidery and quilting techniques that connect her practice and visual language to an ancestral lineage of Black women artists and makers.”

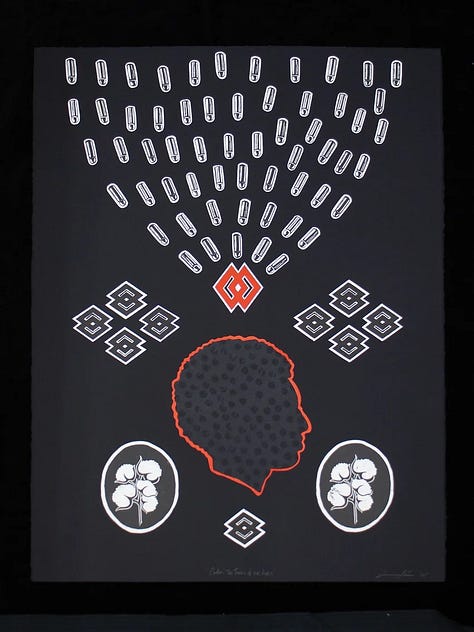

Dr. Deborah Greyson uses printmaking and drawing to “[capture'] the nuance, beauty and dimensionality of Black lives that often gets drowned out by the necessity of always having to say truly obvious and basic things like Black lives matter.” Dr. Greyson’s collection “Dreams and Reckonings,” inspired by the events of racial violence, “racial reckoning,” and resistance during the pandemic, explores the ways in which grief, rage, and joy exist in the mind and body, and what it is like for her “to have to learn to hold them all at the same time.”

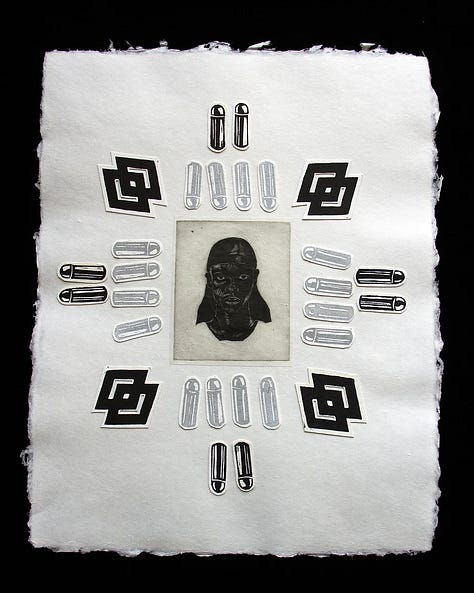

Finally, Karen J. Revis is a printmaker based in New York City who is primarily “driven by process and materials.” Revis began a series in 2017 called REVISionary Prints, which explores her “experience growing up in an all black community in the 60’s and being black and existing in today's political climate.” She uses techniques like “linoleum cuts, monoprints, paper lithograph,” often on handmade paper.

Connecting with Althea was the great joy of my visit to the print fair, and I’ve loved diving deep into her work and into the archives of the 5 other printmakers that make up Black Women of Print. I hope you check out their work - they are all phenomenal artists with clear visions, powerful references, and true technical skill.

Excited about this new series

So beyonddd cool